Margin of Safety as the Central principle of Value investing.

Margin of safety is a core principle of value investing, originally articulated by Benjamin Graham and later championed by investors like Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Seth Klarman, and many others. At its essence, margin of safety means buying an investment at a significant discount to its intrinsic value to provide a cushion against errors in analysis or unforeseen bad luck. As Graham famously wrote, “Confronted with a challenge to distill the secret of sound investment into three words, we venture the motto: Margin of Safety.” Warren Buffett echoed this decades later, affirming that those are indeed “the right three words” in investing. This report will compare how legendary value investors define and apply margin of safety in their stock selection and valuation methods, how these strategies evolved over time, and how they implement practical techniques (from net-nets to discounted cash flows) to ensure they never overpay. We’ll also highlight examples and case studies illustrating each approach, and compare the similarities and differences in their investing styles (quantitative vs. qualitative focus, levels of conservatism, etc.).

Benjamin Graham: The Father of Margin of Safety

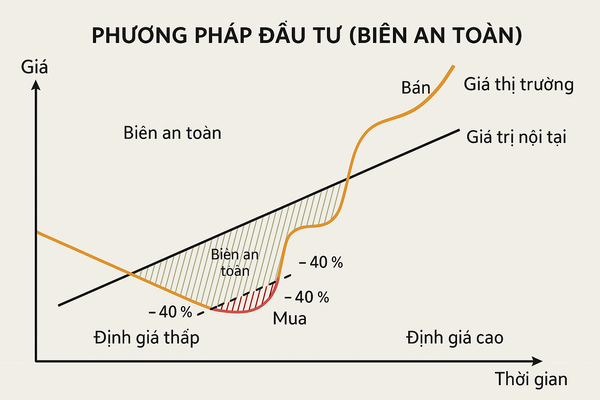

Benjamin Graham (author of Security Analysis and The Intelligent Investor) introduced margin of safety as the central concept of investment. Graham observed that because the future is uncertain and investors are often irrational, one should buy well below a stock’s intrinsic value to allow “room for human error”. In practical terms, Graham’s margin of safety is the gap between a company’s intrinsic value (ascertained through fundamental analysis) and the market price. The larger this gap, the more protection the investor has if the business hits a rough patch or if the initial analysis was too optimistic.

How Graham Defined Intrinsic Value: Graham typically estimated intrinsic value based on assets and earnings. He often assumed little to no growth to be conservative. For example, one heuristic from Graham’s early writings is:

- Intrinsic Value ≈ Earnings per Share × (8.5 + 2×Growth Rate).This was a simplified formula suggesting what a stable company might be worth given a no-growth P/E of 8.5 and an adjustment for growth. Importantly, it was a starting point – Graham insisted on a margin of safety on top of such estimates, not paying full intrinsic value. (He later adjusted this formula to account for interest rates, but in all cases he advocated caution in its application.)

- “Net-Nets” (Net Current Asset Value): Graham’s signature strategy was buying companies for less than their net current assets. He would calculate a firm’s Net Current Asset Value (NCAV) = Current Assets – Total Liabilities (essentially liquidation value of the working capital), and only buy if the stock traded at a steep discount to that. In fact, “Graham normally bought stocks trading at two-thirds of their net-net value as his margin of safety cushion.” In other words, if a company’s NCAV was $30 per share, Graham might not pay more than ~$20 per share (around 2/3 of NCAV). This ensured that even if the company’s earnings disappeared, the hard assets (cash, inventory, receivables) backing the stock greatly exceeded the price paid. It’s the ultimate quantitative margin of safety – the stock is worth more “dead” (liquidated) than alive.

Stock Selection and Implementation: Graham laid out strict criteria to find such bargain stocks, especially for the defensive investor. Some guidelines included:

- Buying companies with strong balance sheets (e.g. current ratio > 2, low debt) and a history of positive earnings and dividends.

- Seeking low valuation multiples – for instance, stocks with P/E ratios < 15 and price-to-book ratios < 1.5, or even better, those trading below book value or NCAV.

- Diversifying widely to mitigate risk. Graham knew that some cheap stocks could still deteriorate or even go bankrupt, so he often held a basket of 20–30 or more such stocks. By spreading out, the portfolio’s margin of safety was improved – losses on a few would be offset by gains on others, and on average the deeply discounted purchases paid off.

Example – Graham’s Net-Net Approach in Action: During the Great Depression and its aftermath, many public companies traded at extreme discounts. Graham famously bought shares of companies like Northern Pipeline and others that held more cash and assets on their books than their entire market capitalization. By purchasing at say 50–60 cents on the dollar of conservative asset value, Graham locked in a margin of safety – even if these companies were liquidated, the proceeds per share would exceed his purchase price. One rule of thumb from Graham’s era was to buy at a 30% to 50% discount to calculated fair value. This cushion meant that if his valuation was off or the business hit “worse than average luck,” the investment would still not be a disaster. Graham described this principle using an engineering analogy: a bridge built to carry 30,000 pounds should only have 10,000 pound trucks driving over it. Likewise, an investor should not push a financial decision to its limit – always leave a safety margin.

Graham’s approach was highly quantitative and conservative. He cared little about a company’s glamour or growth prospects if the numbers showed undervaluation. In his own words, “to have a true investment, there must be a true margin of safety” – meaning that intrinsic value, calculated conservatively, must considerably exceed the price paid. This disciplined focus on low price relative to value “ensures a margin of safety” in his investments. It also shaped the next generations of value investors, including his student Warren Buffett.

Warren Buffett: Evolving from Cigar Butts to Great Companies

Warren Buffett, Graham’s most famous disciple, often calls margin of safety the “bedrock” of his investing philosophy. He initially started by strict Graham-style investing – buying “cigar butt” stocks that were very cheap statistically – but over time, Buffett (influenced by Charlie Munger) transitioned to buying quality companies at fair prices. Despite this evolution, the margin of safety principle remained central: Buffett “only [acquires] stocks and entire businesses when they can be obtained at a noteworthy discount to ... true intrinsic value”, a concept he considers “the central concept of investment”.

Defining Intrinsic Value (Buffett’s Approach): Buffett expanded the notion of intrinsic value to be the present value of future cash flows of a business. He describes intrinsic value as the discounted cash that can be taken out of a business during its remaining life – essentially a DCF (Discounted Cash Flow) valuation. If he can estimate those future cash flows (using conservative assumptions) and discount them at an appropriate rate (often a reasonable expected return like 10%), that gives a measure of what the business is worth. The margin of safety is achieved by paying much less than that intrinsic value estimate.

- In Buffett’s words, “We insist on a margin of safety in terms of a purchase price that’s an appropriate discount from the intrinsic value of a business.” He often reiterates Graham’s mantra that price is what you pay, value is what you get – and you should never confuse the two. By buying at a price well below his appraisal of value, Buffett ensures that even if his estimates are slightly wrong or if the company faces a setback, the investment should still yield a satisfactory result.

From Graham’s Strict Criteria to Quality Focus: In the 1950s and 1960s, Buffett’s partnership dutifully applied Graham’s tactics. He even noted a simple formula akin to Graham’s net-net approach: a stock should be bought at roughly one-third of its net working capital as a rough yardstick for safety. In those days, Buffett scoured for tiny, overlooked companies selling for less than their tangible assets – classic margin-of-safety plays. For example, early in his career Buffett bought Sanborn Map, a company whose investment portfolio alone was worth more than its stock price. Such opportunities provided an automatic cushion.

However, as these deep value “cigar butts” became harder to find and as Buffett’s capital grew, he shifted strategy. With Charlie Munger’s influence, he started seeking wonderful businesses at fair prices, rather than just fair businesses at wonderful (fire-sale) prices. But crucially, “fair price” still meant a price below the business’s true worth. Buffett would calculate what a high-quality company’s future earnings were likely to be (taking into account its competitive moat and growth prospects), and then only buy if there was a significant gap between that intrinsic value and the current price. He states this plainly: “We don’t have to be smarter than the rest; we have to be more disciplined. We don’t get paid for activity, just for being right. As long as we insist on a margin of safety in our purchase price, we can make few investments and still do well.” (This ethos reflects patience and selectivity – waiting for the fat pitch.)

Buffett’s Implementation of Margin of Safety:

- Qualitative + Quantitative Analysis: Buffett’s stock selection became a blend of quantitative analysis (examining financials, cash flows, returns on equity, etc.) and qualitative judgment (assessing the strength of the business franchise, quality of management, and long-term prospects). He focuses on companies with durable competitive advantages (brands, cost advantages, etc.), because a strong business is more predictable – and predictability reduces the risk of surprises. In Buffett’s view, understanding a business well effectively reduces the required margin of safety, whereas if a business is hard to predict, one should demand an extra-large discount. “The less [one] understands a business, the larger the margin of safety needs to be,” he said, using the analogy that you build a bridge to hold 30,000 pounds but drive 10,000-pound trucks across it.

- Valuation Method: Buffett doesn’t rely on any single formula these days; instead, he uses a DCF-like approach combined with a threshold for acceptable returns. He has mentioned looking for an “earnings power ... that even under depressed conditions yields an adequate return” on the price paid. This means he might stress-test a company’s earnings (e.g. assume a recession scenario) and ensure the investment would still earn a decent yield on cost. If a company’s “earnings yield” (earnings/price) under a cautious scenario is, say, 10% or higher, and its long-term prospects are good, Buffett would see that as a favorable gap versus, for instance, a risk-free rate. By requiring a margin in the yield or cash flow relative to the price, he guards against downside. In practice, Buffett has indicated that most value investors seek on the order of a 20–30% discount to intrinsic value, but he personally aims for as big a discount as possible. (E.g., if he figures a business is worth $100 per share, he might wait to buy until it’s $70 or less – the bigger the gap, the better).

- Concentration and Conviction: Unlike Graham, who diversified heavily, Buffett became more concentrated. He might put a large portion of his portfolio in just 5–10 stocks that clear his high bar. His view is that if you thoroughly understand a great business and have a huge margin of safety, you should load up on it. This concentration is only safe because of the margin of safety principle – each investment is made with a significant cushion and high conviction. (Buffett’s first rule is “never lose money,” and the second rule is “never forget rule #1.” This is essentially another way of saying always have a margin of safety to protect the downside.)

- Example – Buffett’s Washington Post Investment: A classic case study Buffett often cites is his 1973 purchase of Washington Post Co. During a severe bear market, WaPo’s stock had fallen dramatically. Buffett calculated that the company’s real intrinsic business value was around 4 times the market price at the time. In his 1985 letter he wrote, “We bought our Washington Post holdings at a price not more than one-fourth of the then per-share business value of the enterprise... Most analysts would have estimated WPC’s intrinsic value at $400–$500 million, and its $100 million stock market valuation was plain to see. Our advantage was attitude: we had learned from Ben Graham that the key to successful investing was buying at a large discount from underlying business value.” Here, Buffett seized a 75% margin of safety (price was only 25% of intrinsic value). Even though the stock could have always fallen further in the short term, the gap was so wide that over time the market corrected – by 1985 his $10.6 million investment had grown to $221 million. The downside risk was minimal because the assets (newspaper, TV stations, etc.) were unquestionably worth far more than $100 million, and indeed the company kept growing its value. This example shows Buffett still applying Graham’s margin-of-safety logic, just now to a high-quality media business.

- Example – Buffett in a Crisis (American Express 1964): Another famous early Buffett move: In 1964, American Express shares were pummeled by the “Salad Oil Scandal,” losing about half their value as investors feared AmEx would owe millions in payouts. Buffett analyzed the situation and concluded that the core business of AmEx (the charge card franchise) was strong and the loss, while painful, was survivable. At the panic lows, the stock was trading far below what Buffett reckoned its true value was, considering the strength of the brand and future earnings power. He invested 40% of his partnership’s capital into AmEx. This was a bold but classic margin of safety play – buy when others are fearful if you’re confident the intrinsic value is much higher. Within a year or two, AmEx had stabilized and the stock tripled. Buffett’s margin of safety was the huge discount due to temporary hysteria. Even if AmEx had taken longer to recover, the downside was limited by the company’s durable business, and the upside was very high once normalcy returned.

Buffett’s Style in Summary: Buffett still preaches Graham’s core ideas (“never rely on the kindness of strangers (the market) to pay you back, instead build your own safety net by buying under value”). However, he broadened the concept to include qualitative factors: a high-quality business provides an additional margin of safety because it is less likely to deteriorate unexpectedly. He is willing to pay a bit more (closer to fair value) for an excellent company, whereas Graham would only buy the absolute cheapest companies regardless of quality. In Buffett’s practice, margin of safety comes from both paying a low price and choosing businesses with inherently low risk (strong competitive positions, predictable earnings). This approach has proven enormously successful – as of 2023, Berkshire Hathaway’s stock compounded at over 20% annually since 1965, largely attributable to buying with a margin of safety and holding for the long term.

Charlie Munger: Quality and the Multi-Faceted Margin of Safety

Charlie Munger, Buffett’s right-hand man, is another legendary value investor who strongly espouses margin of safety – calling it a principle that “will never be obsolete.” Munger’s contribution was to emphasize quality and a multidisciplinary understanding as key elements of safety. He agrees completely with Graham’s and Buffett’s tenet that you must buy at a discount to intrinsic value, but he adds that intrinsic value itself should be assessed with a wide lens (considering qualitative factors, durability, etc.). In other words, better businesses make for safer investments, and one should still insist on getting them at a discount.

Munger often enumerates four criteria for an investment: “We have to deal in things that we are capable of understanding. ... that have a business with some intrinsic characteristics that give it a durable competitive advantage. ... run by able and honest people. ... and available at a price that makes sense and gives a margin of safety.”. That fourth filter is pure Graham – even the best business is not worth an infinite price.

Margin of Safety, the Evolved View: Munger explicitly notes that the application of margin of safety evolved from Graham’s day: “What Graham did in his era was quite different from the way Buffett and Munger use it today. In the aftermath of the Depression Graham was looking for companies ‘worth more dead than alive.’ ... As years passed those cigar butts disappeared. Buffett, encouraged by Munger, began to apply the same principle to high-quality companies, and the process worked just as well.”. In other words, Graham’s margin of safety was in undervalued assets, whereas Buffett and Munger find margin of safety in undervalued earnings power of great businesses. Munger joked that Graham’s disciples “kept changing the definition [of a bargain] so they could keep doing what they’d always done. And it still worked pretty well.” – meaning they went from buying below book value, to buying at low P/E, to buying high-quality franchises at reasonable P/E, all the while insisting on a value gap between price and what a rational appraisal would estimate.

Key aspects of Munger’s approach:

- Focus on Quality as Safety: Munger argues that a great business carries its own form of safety. A company with a dominant market position, pricing power, and consistent growth is less likely to suffer a permanent loss of value than a mediocre company selling at a rock-bottom price. For example, Coca-Cola’s brand or See’s Candies’ loyal customer base create a resilience – an investor in such a company can have more confidence in the future earnings, which in turn justifies projecting a higher intrinsic value. Thus, Munger is willing to pay, say, 90 cents for a dollar of intrinsic value if that intrinsic value is rock-solid and likely to grow, whereas Graham might insist on paying 50 cents for a dollar of value in a weak company. Nonetheless, Munger still prefers to pay much less than the value; he just defines “value” more generously by considering the intangible strengths of a business (which Graham tended to ignore).

- Deep Understanding to Reduce Risk: Munger is famous for applying mental models from many disciplines (psychology, economics, math, etc.) to understand businesses. He believes thorough analysis and understanding of a company’s risks improve one’s odds – effectively enlarging the margin of safety. He once said, “All intelligent investing is value investing – acquiring more than you pay for. You must value the business to figure out what’s more. And you have to have some parameters around that value (conservatism) and then buy at a significant discount – that’s margin of safety.” In practice, Munger starts by asking “What can go wrong here?” and “What’s the downside?” (much like Klarman, as we’ll see). He avoids businesses that are overly complex or outside his circle of competence, no matter how cheap, because investing in something you don’t fully grasp eliminates your margin of safety.

- Valuation Method: Like Buffett, Munger doesn’t use mechanical formulas; he uses conservative estimates of future earnings or cash flows. He might consider multiple scenarios (e.g. a normal case and a stress case) for a company’s profits. If even the pessimistic scenario yields an adequate return at the purchase price, that price has a margin of safety. For instance, when evaluating a stock, Munger might think: “Is the current price at least 20–30% lower than a conservative value of this business?”. If yes, there’s a margin of safety; if it’s only at par with fair value, any misstep could cause loss. Munger has indicated that requiring a 20–25% discount is a minimum for solid companies – for riskier ones one would need an even bigger gap.

- Example – See’s Candies: This is a favorite Munger example highlighting qualitative margin of safety. In 1972, Berkshire Hathaway acquired See’s Candies for $25 million. By traditional Graham standards, this price was not cheap – it was many times the book value of the company (the factories, inventory, etc. were worth far less than $25M). Buffett almost balked at the price. But Munger saw that See’s had an intangible value: a beloved brand on the West Coast and the ability to raise prices a bit each year without losing customers (pricing power). They estimated See’s could produce substantial free cash flow and grow steadily. In hindsight, that $25M purchase has produced over $2 billion of pretax earnings for Berkshire over the decades. The margin of safety in See’s was not obvious from the balance sheet; it came from the company’s earning power and brand durability, which made its true intrinsic value far higher than the accounting numbers suggested. Munger and Buffett paid what looked like a full price at the time (about 12–13 times earnings), but because the earnings were reliable and growing, the intrinsic value was well above what they paid. Lesson: A high-quality business can offer a margin of safety through future growth and resilient economics, even if not selling at fire-sale multiples. Munger has since used See’s to illustrate that paying up (within reason) for quality is safer than buying a statistically cheap but inferior business.

- Risk Management and Temperament: Munger emphasizes temperament as part of investing safely. He warns against emotional or herd-based decisions. In his view, many investors abandon safety margins in euphoric times by assuming “this time is different” – a very dangerous phrase he warns against. He quips that in engineering people take safety seriously, but in finance they often don’t until after disaster strikes. Munger’s strategy is to always be conservative and skeptical of rosy forecasts. He preaches that not losing money is just as important as making money. By avoiding big mistakes (through margin of safety and prudent analysis), an investor’s results over the long run will compound impressively. This aligns with his famous rule: “The first rule of investing is don’t make big mistakes, and the second rule is the same as the first.” In practice, this means never violate margin of safety – don’t get so excited about a company that you pay a price that assumes perfection. As Seth Klarman later put it, “You would never want your investment fortunes to be dependent on everything going perfectly, every assumption proving accurate, every break going your way”.

In summary, Charlie Munger’s style is a blend of Graham’s prudence and Phil Fisher’s focus on quality growth. He elevated the margin of safety concept from a purely numeric buffer to a more holistic idea: build multiple layers of safety – buy a great business (quality safety) at a good price (valuation safety) while understanding it deeply (knowledge safety). He firmly believes that no matter how good the business, one must not overpay, i.e., one must incorporate a margin of safety in the price. This approach has guided Berkshire Hathaway’s phenomenal investments alongside Buffett.

Seth Klarman: “Margin of Safety” as a Way of Life

Seth Klarman, manager of the Baupost Group and author of the famous book “Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor”, is often considered a spiritual heir to Graham’s and Buffett’s principles. Klarman’s entire investment philosophy “centers on the margin of safety, a disciplined approach to minimize risk while maximizing returns.” In fact, he insists on exceptionally large margins of safety, often seeking stocks at 50% or less of his intrinsic value estimate – an even more conservative stance than Graham’s or Buffett’s in practice. Klarman’s approach could be described as deep value with a dash of cynicism: he assumes things will go wrong and positions his portfolio to be protected when they do.

Defining Margin of Safety (Klarman’s view): Klarman echoes Graham in defining margin of safety as purchasing securities “at prices sufficiently below underlying value to allow for human error, bad luck, or extreme volatility in a complex, unpredictable world.” In other words, if Klarman calculates that a stock’s underlying business value is $100, he might only be interested in buying it at $50 or $60 – a 40-50% discount – to cover any mistakes in his analysis or unexpected adverse events. He believes this is what separates true investing from speculation: the insistence on a bargain relative to conservative value.

How Klarman Finds Intrinsic Value: He is very flexible and agnostic about methodology – he’ll use whatever valuation approach fits the situation, as long as it’s conservative:

- For a stable operating business, he might use DCF or earnings-based valuations, but with cautious inputs (low growth rates, high discount rates, or “haircuts” to uncertain cash flows). He stresses that any valuation is just an estimate, so he wants a big gap between his estimate and the price.

- For asset-rich companies or potential liquidations, he’ll focus on balance sheet values (tangible book, liquidation value of assets). If a stock sells for half of its tangible book value and he judges those assets are real and maybe salable, that’s a clear margin of safety.

- In distressed debt or special situations (Klarman often ventures outside common stocks), he looks at recovery value. For example, if he can buy a bond for 30 cents on the dollar of face value, and his analysis of the company’s finances suggests it will recover at least 60 cents in a restructuring, that’s a huge margin of safety.

- He also pays attention to catalysts – something that might unlock the value – though he doesn’t require it. A catalyst (like an announced asset sale, spinoff, liquidation, or activist involvement) can shorten the time needed for the margin of safety to be realized, reducing the risk of waiting indefinitely.

Klarman’s Implementation and Tactics:

- Wide Margin Requirements: Klarman sets a high bar. While many value investors are content with a 20-30% discount, “Klarman sets his sights significantly wider... targeting discounts as high as 50% or more to intrinsic value”. This means he often looks at very out-of-favor assets – those that other investors shun. It also means he ends up holding a lot of cash when he can’t find opportunities that meet his criteria. He’s famously comfortable holding double-digit percentages of his portfolio in cash or cash-like securities if markets are overvalued. This patience is itself a risk-management tool: holding cash when no significant bargains exist effectively preserves capital and improves the overall margin of safety of the portfolio.

- Deep Research and Conservative Assumptions: Klarman’s team performs exhaustive bottom-up research on each investment. They look for mispriced bets – where the market price implies a very pessimistic scenario. For instance, during a market crash, a stock might trade as if the company’s earnings will never recover (pricing in a “worst case”). Klarman likes those scenarios because “in market declines, stocks are often priced as if nothing can go right. They have the widest margin of safety and lowest risk because the worst-case scenario is already priced in.” This was evident in 2008–2009: Baupost bought distressed debt and beaten-down stocks when fear was rampant, locking in huge margins of safety (and later outsized gains when conditions normalized).When valuing, Klarman always considers the worst-case or liquidation value: “Always do conservative valuations, with the worst-case scenario or liquidation value in mind.” He then requires a wider margin if there are extra risks on the horizon (for example, in times of deflation or economic uncertainty, he’ll demand an even deeper discount). This systematic low-balling of values and high-balling of required discounts means that many potential investments get rejected – only the most mispriced make it into the portfolio.

- Diversification and Hedging: While Klarman often runs a concentrated portfolio of his best ideas, he also believes in not putting all eggs in one basket. He will spread bets across different categories (some equities, some debt, some real estate or other assets) that each have their own margin of safety. He’s also been known to hedge certain risks – for example, using market put options or short positions as insurance against a broad market crash when the portfolio has a lot of long exposure. In Klarman’s view, nothing is off the table if it helps protect the downside. “Risk can’t be reduced to a number... unknowns exist. That’s why margin of safety, diversification, and hedging are important.”

- Selling Discipline: Part of maintaining a margin of safety is knowing when it’s gone. Klarman is quick to sell a holding once it approaches intrinsic value. He’d rather rotate into a new undervalued position than ride a winner until it possibly becomes overvalued. He notes that replacing holdings with better opportunities and selling once value is realized can continually improve the margin of safety of the portfolio. This contrasts with Buffett, who might hold a great company indefinitely even past its fair value; Klarman is more likely to take profits and move on, given his focus on the initial margin at purchase.

- Example – Baupost in Action: One illustrative example was Klarman’s strategy around the 2008 financial crisis. Going into 2007, he saw few bargains and held a lot of cash. When the crisis hit and asset prices plummeted, Baupost deployed capital into various distressed opportunities: mortgage securities, corporate debt, and deeply discounted equities. A reported example was buying Lehman Brothers bonds after its bankruptcy – these were trading at a small fraction of face value. Klarman purchased them when most investors were panicking, effectively paying perhaps 20 cents on the dollar. Later, as the assets were unwound, recoveries were significantly higher, yielding huge returns. The margin of safety was apparent: at 20 cents, even a fire-sale of Lehman’s remaining assets was likely to pay more than that. Similarly, he bought beaten-down equities like pharmaceutical royalties and post-bankruptcy equities, where his downside was protected by asset values or hard contracts. By 2010, Baupost had significantly profited from these moves. Another case: in the late 1990s tech bubble, Klarman famously refused to buy into dot-com mania and instead held cash and value stocks. His relative performance lagged in the boom, but when the bubble burst, Baupost had no losses from it and plenty of cash to scoop up bargains from the wreckage – a direct result of adhering to margin of safety and not overpaying despite the crowd’s behavior.

Klarman’s style can be described as extremely risk-averse and opportunistic. He demands a margin of safety in every investment, thinking like a pessimist upfront so he can behave like an optimist when the odds are heavily in his favor. He writes, “The best investments have a considerable margin of safety. This is Benjamin Graham’s concept of buying at a sufficient discount that even bad luck or the vicissitudes of the business cycle won’t derail an investment.” He even invokes the same bridge analogy: you don’t want your investment outcomes to depend on everything going perfectly. By insisting on a large margin, Klarman aims to make his portfolio “tremendously resilient against permanent loss” while still positioning for “dramatic upside” when the market recognizes the mispricing. This approach has yielded one of the best long-term track records in investing (Baupost’s returns since inception in 1983 are reportedly in the high teens with very low volatility).

Other Notable Value Investors and Their Margin of Safety Mantras

Beyond the four luminaries above, many other prominent value investors have championed margin of safety in their own styles. Here are a few examples:

- Walter Schloss (Graham Disciple): Walter Schloss is often cited in Buffett’s essays as a “superinvestor” of Graham-and-Doddsville. Schloss strictly applied Graham’s techniques well into the late 20th century. He focused on “buying stocks at prices significantly lower than their intrinsic value, ensuring a margin of safety” – often targeting companies at 20% or more below book value, with little debt. Schloss ran a very diversified portfolio of dozens (even hundreds) of these deep value stocks. His simple mantra was price versus value: if a stock was cheap enough based on assets or earnings, he bought it, trusting that eventually the market would correct the mispricing. By holding many positions, he further mitigated risk – even if a few went wrong, the overall portfolio returns were excellent. This ultra-conservative, numbers-driven approach led Schloss to compound money at ~15% annually over 5 decades, rivaling Buffett’s record, all without ever talking to management or trying to predict the future. It underscores that Graham’s original margin of safety formula (low price relative to asset value + diversification) remained viable for decades.

- Howard Marks (Oaktree Capital): Howard Marks, a famous investor in distressed debt and author of The Most Important Thing, emphasizes risk control as the primary job of an investor. His version of margin of safety often comes in the form of buying when prices are low relative to fundamentals, thereby reducing downside risk. He succinctly says, “Low price is the ultimate source of margin for error.” Marks applies this in credit markets by purchasing bonds or loans at deep discounts (thus with high yields or strong collateral coverage). By doing so, even if the situation deteriorates, the price paid already reflects a worst-case scenario, and the investor is protected. Marks, like Klarman, focuses on not losing money; he often quotes Buffett’s rules #1 and #2. In equity terms, Marks would advise only buying stocks that appear significantly undervalued and not chasing hot stocks – a philosophy very much aligned with margin of safety. His memos often illustrate how investors get in trouble by paying high prices (no safety margin) in good times, and how one should instead “buy when there’s blood in the streets” (maximum safety margin due to low price).

- Joel Greenblatt: Greenblatt, known for the “Magic Formula” and author of You Can Be a Stock Market Genius, took margin of safety into a slightly more systematic realm. His Magic Formula strategy looks for companies with high earnings yield and high return on capital – effectively combining value and quality in one screen. The logic is that such companies are “good and cheap,” meaning the market price is low relative to current earnings (value factor) and the company’s economics are strong (quality factor). While Greenblatt doesn’t explicitly talk about margin of safety in emotional terms, the Magic Formula is built on its principles: a high earnings yield (like a low P/E ratio) provides a buffer if earnings falter, and strong profitability means the business is likely solid, providing a cushion against competitive or financial stress. Greenblatt has said that buying a basket of top Magic Formula stocks each year has yielded excellent returns historically, precisely because it consistently buys businesses at a discount to their fair value (the low price relative to their quality gives them an edge). This is essentially a heuristic-driven margin of safety approach – rather than deeply analyzing each company, Greenblatt’s method assumes that buying statistically cheap, high-quality companies in bulk will on average provide the margin of safety needed to outperform. And indeed, in his backtests and real-world results, this approach did well, validating Graham’s notion that buying cheap works over time.

- Mohnish Pabrai: A devoted follower of Buffett and Munger, Pabrai sums up margin of safety with the phrase “Heads I win, tails I don’t lose much.” This means he looks for investment situations where the upside is large but the downside is very limited. Pabrai often hunts for special situations or beaten-down stocks that have a fixable problem. For example, he has invested in spinoffs or companies emerging from bankruptcy that still have solid assets or businesses. By paying extremely low valuations, he ensures that even if things don’t go great (tails), the value of assets or a breakup value covers his purchase price (so he doesn’t lose much). But if things go well or normal (heads), the stock could rally significantly (he wins big). This asymmetric payoff approach is essentially margin of safety in practice – invest only when you have a favorable imbalance between potential reward and risk. Pabrai also emulates Buffett’s focus on circle of competence; he won’t invest in businesses he can’t understand. That itself is a risk-reduction technique. He also notes that many business schools mistakenly teach that higher returns require higher risk, whereas in reality the best value investors seek low-risk, high-return bets – exactly what margin of safety is about.

- Bruce Berkowitz: Berkowitz, manager of the Fairholme Fund, became famous after the 2008-09 crisis for big bets on AIG, Bank of America, and other distressed financials – all of which paid off handsomely. His mantra: “Is there a sufficient margin of safety?” guides every investment. Berkowitz tends to run a very concentrated portfolio (only 10 or 20 names at times), which means each position must have a huge margin of safety because there’s little diversification. For instance, when he bought AIG in 2010, the stock was trading at a fraction of its book value because investors feared it was uninvestable after the bailout. Berkowitz analyzed AIG’s businesses and concluded that the core insurance units were sound and the book value was real; as the crisis eased, AIG’s intrinsic value would shine through. He bought in when AIG was extremely cheap and held on – this required conviction in his valuation. Within a few years, AIG’s stock had multiplied from his purchase price. Berkowitz’s success (and occasional struggles) underscore that concentration demands margin of safety. If one of his big bets was wrong, it would hurt the fund badly – so he tries to only invest when the odds are overwhelmingly in his favor (i.e., price is way below conservative value).

- Li Lu: Li Lu is a value investor often mentioned as “the Chinese Warren Buffett” (he also manages some of Charlie Munger’s family money). Li Lu’s quote, “If you buy a stock with a sufficient margin of safety, the probability is with you,” reflects the statistical view of margin of safety. It’s about stacking the odds. He, like others, looks for companies that are undervalued relative to their true worth and strong in fundamentals. By doing so consistently, he knows that while any single investment could have unforeseen problems, over a portfolio of many such bargains the probabilities favor good outcomes (mean reversion, market recognition of value, etc.).

Each of these investors, in their own way, upholds the margin of safety principle. Some lean more quantitative (Schloss, Greenblatt), some more qualitative (Pabrai, Berkowitz), but all insist on not paying full price for an asset – they seek that gap between what they pay and what they get. It’s also noteworthy that many of them draw the line between investing and speculating at margin of safety: if you’re buying without a cushion (just hoping something will go up), you’re speculating; if you’re buying with a cushion, you’re investing. This ethos has been passed down from Graham to the current generations.

Comparing Strategies: Evolution, Similarities, and Differences

All of the above value investors share a common philosophical foundation – they aim to preserve capital and avoid permanent losses by buying with a margin of safety. However, their strategies and styles have notable differences. Below is a comparison of how margin of safety is defined and applied across these legendary investors, and how their approaches evolved over time:

Common Ground – Similarities in Margin of Safety Philosophy

- Capital Preservation First: Every one of these investors emphasizes not losing money. The margin of safety is fundamentally about downside protection. Whether it’s Graham refusing to buy without a 30%+ discount, Buffett’s rule #1, Munger’s engineering analogies, or Klarman’s risk aversion, the primary goal is the same: ensure that even if things go wrong, the investment won’t be catastrophic. As Klarman writes, a margin of safety “allows for imperfection, error, bad luck or excessive volatility in order to avoid big losses.” Preservation of capital is “built-in and necessary” because the future is unpredictable and even great investors make mistakes.

- Intrinsic Value as the Benchmark: All use the concept of intrinsic value to anchor their decisions. They might calculate it differently (asset value, earnings power, DCF, etc.), but they each assess what a business is worth and compare it to price. Buying below intrinsic value is the essence of margin of safety. None of them rely on market momentum or greater-fool theory; they all root their strategy in fundamental valuation.

- Conservative Assumptions: When estimating intrinsic value, they err on the side of conservatism. Graham assumed no growth; Buffett uses cautious forecasts and higher discount rates if unsure; Munger assumes things will get tough at some point (distress scenario); Klarman basically assumes Murphy’s Law (whatever can go wrong, might). This conservatism means their intrinsic value estimates are often lower than an optimist’s estimate – which in turn means a given market price will look even more attractive if it’s below that conservative intrinsic value. For example, two analysts might value the same stock: a bullish one says $100, a conservative one (in the Graham/Klarman mold) might say $70. If the stock is $50, the bullish person thinks there’s a 50% margin, the conservative sees a 40% margin. By using the lower $70 figure as the yardstick, the value investor is being extra safe. As Michael Mauboussin noted (quoting Graham), the margin of safety is there to “absorb the effect of miscalculations or worse-than-average luck.”

- Patience and Discipline: They are all willing to wait for the right opportunity and then act decisively. None of these investors feels compelled to always be fully invested if bargains aren’t available. Graham held cash or bonds in between opportunities; Buffett sat on piles of cash in recent years waiting for a big elephant to bag; Klarman often holds cash and even returned money to investors when he couldn’t find good deals. This patience is critical because margin of safety opportunities are not always abundant – one must sometimes sit on the sidelines during euphoric markets. They also all resist the temptation to chase stocks without a margin of safety. In frothy markets, they’ll risk underperforming or looking foolish rather than compromise their principles.

- Contrarian Tendencies: Buying with a margin of safety often means going against the crowd, because you’re buying things that are out of favor (that’s usually why they’re cheap). All these investors have a contrarian streak. Graham bought in the Depression when everyone hated stocks. Buffett and Munger bought stocks like Washington Post or Coca-Cola when the market had undervalued them (often amid pessimism or neglect). Klarman actively seeks what others are dumping. This doesn’t mean they buy anything that’s down – but they are willing to look in areas that are unpopular if that’s where the value is. They “buy from pessimists and sell to optimists,” as Graham put it.

- Knowledge and Circle of Competence: Each recognizes the importance of sticking to what you understand. Buying with a margin of safety doesn’t help you if you mis-evaluate the business in the first place. Graham stuck largely to industrial and financial companies with straightforward accounts. Buffett avoids tech companies he doesn’t “get” (until recently) and famously skipped the dot-com bubble entirely. Munger stresses multidisciplinary knowledge but also says to avoid what you can’t figure out. Klarman often plays in areas (like distressed assets) where he has deep expertise and others don’t. This focus means their analyses – and thus their intrinsic value estimates – are more likely to be accurate, which makes the margin of safety real. In other words, knowing your circle of competence is itself a margin of safety (it prevents venturing into risky unknowns).

- Emotion Management: All stress the importance of controlling emotions – fear and greed – in order to stick to margin-of-safety investing. It’s psychologically hard to buy what’s unloved and to sell or abstain when others are exuberant. But these investors have done so repeatedly. They treat Mr. Market as a servant, not a guide, taking advantage of the market’s foolish pricing rather than getting swept up in it. This temperament is a shared trait that allows them to actually execute on buying with a margin of safety.

Key Differences and Evolution of Strategies

Despite the common core, there are important differences in how each applies margin of safety:

- What They Consider “Value”: Graham was very balance-sheet focused (tangible assets, working capital). For him, margin of safety = buy below liquidation value. Buffett and Munger became more earnings and quality focused – for them, margin of safety = buy a good business at a price that implies very conservative earnings assumptions. Seth Klarman will use whichever is most relevant – sometimes asset value, sometimes earnings, sometimes sum-of-parts – but always haircuts everything heavily. Modern value investors like Greenblatt or Pabrai might use blended metrics or special situation angles. Evolution: The definition of intrinsic value expanded over time. In Graham’s era (1930s-40s), intangible assets or growth were largely ignored; by Buffett/Munger’s prime (1970s-80s), intangible value (brand, moat, etc.) was recognized as real, so they factored that in and were willing to pay for it – but still below its worth. This is why Graham’s students “changed the definition” of a bargain, as Munger quipped. The common thread is undervaluation, but what is considered “undervalued” shifted from mainly hard assets to include high-quality earnings.

- Margin of Safety Size: Graham typically looked for at least a 30% margin of safety (pay 70 cents on the dollar or better). Buffett hasn’t put an explicit number, but hints at wanting perhaps ~25-30% or more in most cases – he wrote that he seeks businesses that “even under dire conditions” will justify the price, implying the price is maybe 25-40% below normal intrinsic value. Munger has said 20-30% off is okay for great firms, but clearly the more the better. Klarman often prefers 50% off or more. These differences partly reflect opportunity sets and risk appetite: Graham in his time found plenty of 50% off bargains; by Buffett’s time, those were rarer, so 25-30% off a wonderful business was a huge win. Klarman in modern times still finds occasional 50% discounts (often in obscure or distressed areas) and holds out for them. In practice, all want “significant” discounts; the exact threshold is flexible. Notably, as margin of safety percentage goes down, the investor compensates by requiring higher quality and more certainty. For example, Buffett might be okay with only a 20% discount on Coca-Cola because he’s extremely confident in Coke’s brand and steady growth. But if it were a mediocre business, he’d want far more than 20%. Conversely, Klarman with 50% margin often buys pretty uncertain situations – the huge discount compensates for big unknowns.

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative Emphasis: Graham and Schloss were almost entirely quantitative – if the numbers checked out (low price/book, etc.), they often didn’t care to analyze the business qualitatively in depth. Buffett and Munger shifted to a balance of quantitative and qualitative – numbers must make sense, and business quality must be high. Klarman and many modern value investors also blend the two: they scrutinize business quality (to avoid value traps) but also love quantitative bargains. For instance, Klarman might buy a statistically cheap stock but only after understanding why it’s cheap (is it a melting ice cube or just temporarily out of favor?). Greenblatt’s formula quantifies quality (ROC) and value (EY). So, the evolution is from pure quantitative screening (Graham’s checklists) towards integrating qualitative judgment. The trade-off: pure quant gives very objective buy/sell criteria (easy to follow but can miss context), while qualitative can protect you from value traps but demands more skill and can lead to overpaying if you’re too optimistic. The best investors post-Graham learned to marry the two – never abandoning the math, but not being blind to business reality.

- Diversification vs. Concentration: This is a notable difference in implementation of margin of safety. Graham, Schloss, and even Klarman (to a degree) favor broader diversification – holding many positions, each with a margin of safety, to further reduce risk. The margin of safety per stock might be big, but they still don’t want any single mistake to hurt too much. Buffett, Munger, Pabrai, Berkowitz, etc., run concentrated portfolios – they put a lot of eggs in a few baskets and watch them closely. How can they do that? Because they have extremely high conviction in those few bets, built on deep understanding and a large margin of safety. Buffett once said that wide diversification is needed only when investors don’t understand what they’re doing – implying that if you truly have a huge margin of safety and know your pick well, you don’t need 50 stocks. This divergence comes down to personal philosophy. Both approaches worked: Schloss with 100+ stocks at 15% annualized, Buffett with 5–10 stocks at 20%+ annualized. Key point: A margin of safety can be achieved at the portfolio level in different ways. One is many moderately safe bets, the other is a few extremely safe bets. Baupost (Klarman) is interesting because they diversify across asset classes and strategies, but within equities they might still concentrate their biggest conviction ideas.

- Use of Leverage: All these legends generally avoid high leverage – that’s consistent with margin of safety (debt can wipe out even a “safe” investment if things go wrong). Graham recommended minimal or no borrowing for investors. Buffett’s companies use some leverage in insurance float, but Buffett the stock investor rarely uses margin debt to buy stocks. Klarman sometimes uses derivative positions or hedges but not reckless leverage. This is a similarity (aversion to debt) driven by safety, but worth noting as part of style: for them, leverage is the opposite of margin of safety. Howard Marks likes to say if you must lever up an investment to make it attractive, it probably didn’t have a margin of safety to begin with.

- Role of Growth: One subtle difference is how they treat growth in the margin of safety equation. Graham almost ignored potential growth – any growth was gravy on top of a safe asset play. Buffett and Munger actively consider growth as part of intrinsic value (the present value of growing future cash flows) but they require that growth be foreseeable and reliable. Buffett will pay for growth if he’s confident in it (e.g., he paid up for Apple in recent years because of its services growth and loyal customer base – and it paid off hugely). However, paying for growth reduces your margin of safety unless you’re conservative in estimating that growth. So Buffett/Munger make sure to build in a safety margin by using moderate growth estimates, not pie-in-the-sky numbers. Klarman is generally more skeptical of growth projections – he tends to value something on steady-state or only slight growth and treat any rapid growth as uncertain (unless perhaps in special cases). Modern value investors sometimes talk about “Growth at reasonable price (GARP)” – that’s essentially trying to find a margin of safety including moderate growth assumptions. The difference is mostly mindset: Graham started from a pessimistic “no growth” baseline; Buffett/Munger acknowledge growth but handle it cautiously.

- Adaptability to Market Environment: Over time, these investors had to adapt as markets changed. Graham’s tactics worked well in the 1930s-1950s when lots of companies were trading at discounts to assets. By the 1960s, such deep value plays were fewer; Buffett adapted by looking at quality companies (though he still found cigar butts internationally or in small caps at times). In the 1970s, high inflation and changing accounting could make asset values less reliable, so Buffett/Munger really cemented the earnings power approach. In the 1980s and 1990s, Klarman and others found new hunting grounds: distressed debt, thrift conversions, special situations – areas where institutional investors weren’t fully arbitraging away inefficiencies. The concept of buying at a discount remained, but where they applied it shifted. Even today, value investors seek margin of safety in places like spinoffs, micro-caps, out-of-favor sectors (energy in mid-2020, for example, or certain foreign markets). The principle is timeless, but the execution must follow where the mispricings are. For instance, in recent years classic low P/B stocks stayed cheap for long periods (value trap concerns), so some value investors incorporate quality metrics to avoid traps – this is an adaptation building on Munger’s lessons.

- Optimism vs. Pessimism in Style: One could say Graham and Klarman invest with a pessimist’s hat on – always imagining the worst and thus insisting on very low prices. Buffett and Munger invest with a bit more optimism about good businesses – they expect well-run companies to create value over time, so they’re willing to project growth (albeit carefully) and therefore can pay somewhat higher prices relative to current earnings than Graham would. For example, Graham might never have bought Coke at 20x earnings as Buffett did; Graham would consider that too optimistic, whereas Buffett saw decades of growth ahead (rightly so) that made it a bargain. Klarman, on the other hand, might align more with Graham’s skepticism – he’d rather assume nothing good and be pleasantly surprised. Neither approach is “right” or “wrong” – it’s about personality and skill. Importantly, even the “optimists” (Buffett/Munger) are conservative optimists – they don’t count on wild success, just steady continued success of a great firm. And the “pessimists” (Graham/Klarman) are not doomers; they are optimistic that by preparing for the worst, they’ll do well when things turn out normal or good.

The Margin of Safety in Practice – A Concluding Example

To tie everything together, consider a hypothetical stock XYZ Corp and how each investor might evaluate it for margin of safety:

- XYZ Corp has a book value of $50/share, current earnings of $5/share, and is trading at $30.

Graham might note that net current assets are, say, $35/share and no debt. At $30, it’s below NCAV – buy! Even on earnings, P/E = 6, very low. He’d likely purchase, since it’s way below a conservative book/intrinsic value (margin of safety clearly >30%). He might not dig too deep into the business quality; the numbers are enough.

Buffett/Munger would ask: “What’s the nature of XYZ’s business? Are those earnings reliable? Does it have a moat?” If yes (say it’s a stable, boring industry leader temporarily out of favor), they’ll estimate maybe intrinsic value is $60 (using a DCF or comparing to similar companies). At $30, it’s 50% off – an enormous margin of safety for such a good business. They’d load up, possibly even if their intrinsic estimate is only $45 (still a 33% discount). If, however, they find the business is poor or future is shaky, they might pass despite the statistical cheapness, because the quality margin is missing.

Klarman would similarly do a deep dive. If he concludes worst-case liquidation is $40 and ongoing value is $60, buying at $30 is compelling – meets his 50% discount target to ongoing value and even liquidation is higher than price (double margin of safety). He’d also consider if there’s a catalyst: maybe XYZ is considering a sale of a division or activists are circling. That could make it even better. He might also hedge some industry risk if, say, XYZ is an oil company and he’s worried about oil prices – he could buy XYZ and short an oil ETF to lock in primarily the mispricing rather than commodity risk. Graham wouldn’t have hedged; Buffett likely wouldn’t either (he’d just size the position smaller if unsure). Klarman uses every tool to protect downside.

Other investors: A Schloss-type would already have bought at $30 just seeing the low P/B and P/E. A Greenblatt follower would note return on capital and earnings yield – if those are high, it fits the formula, buy it as part of a basket. A Pabrai might like that downside seems limited ($30 vs $50 book) but would want to understand why it’s cheap – maybe it’s facing a lawsuit? If he figures worst-case outcome of the lawsuit still leaves intrinsic > $30, he’ll invest – heads he wins (case resolved, stock to $60), tails he doesn’t lose much ($30 backed by assets).

This scenario shows the spectrum: from purely price-driven decisions (Graham/Schloss) to price and quality-driven (Buffett/Munger) to price and thorough scenario analysis (Klarman). But none of them would pay $60 for XYZ (its estimated intrinsic value) because then there’s no margin of safety. And certainly none would pay $100 on a speculative story, as a pure growth investor might – that’s completely contrary to their discipline.

Final Thoughts

The margin of safety concept has stood the test of time. From Graham’s depression-era bargains to Buffett and Munger’s empire of quality companies bought at discounts, to Klarman’s modern value hunting in all corners of the market, the core idea is unchanged. As Buffett noted, those three words “Margin of Safety” remain the cornerstone of intelligent investing. All these investors have shown in practice that buying undervalued assets with a cushion is a reliable way to achieve superior returns with lower risk. Markets will change, new industries arise, old metrics fall out of favor, but the need for a safety buffer in investing is immutable. In engineering, no one would design a bridge to just barely hold the expected load – they build in redundancy. Likewise, the great value investors always invest with a margin for error.

For anyone looking to apply these lessons: the practical guide is clear. Do your homework to estimate a conservative value for a stock; demand a significant discount before you buy; ensure the company is solid enough to warrant confidence; and stay disciplined about not chasing prices above your comfort zone. If you follow those steps – much as Graham, Buffett, Munger, Klarman and others have done – you tilt the odds of investing success in your favor. In the end, margin of safety is both a technique and a mindset: quantitatively, it’s the difference between value and price; psychologically, it’s the humility to know your own fallibility and insist on a buffer. Adopting this approach helps investors “sleep well at night”, knowing that even if the market throws curveballs, their portfolio has some protection built in. And, as history shows, it’s also a pathway to outstanding long-term returns – truly the best of both worlds.

Sources:

- Benjamin Graham’s principles and original definitions (Who Was Benjamin Graham?) (Who Was Benjamin Graham?) (Why Seth Klarman Swears by the Margin of Safety)

- Warren Buffett’s interpretation and examples (Warren Buffett's 'Margin Of Safety' Principle In Investing: What It Means And Why It Matters By Benzinga) (Warren Buffett's 'Margin Of Safety' Principle In Investing: What It Means And Why It Matters By Benzinga) (Warren Buffett: WPC: From $10.6 Million to $221 Million | The Acquirer's Multiple®)

- Charlie Munger’s perspective and quotes (Charlie Munger on Margin of Safety (the Fourth Essential Filter) – 25iq) (Charlie Munger on Margin of Safety (the Fourth Essential Filter) – 25iq) (Margin Of Safety - Quotes From Klarman, Buffett, Greenblatt & More)

- Seth Klarman’s approach and quotes (Charlie Munger on Margin of Safety (the Fourth Essential Filter) – 25iq) (Why Seth Klarman Swears by the Margin of Safety) (Margin Of Safety - Quotes From Klarman, Buffett, Greenblatt & More)

- Other investors’ quotes: Howard Marks, Walter Schloss, etc. (Margin Of Safety - Quotes From Klarman, Buffett, Greenblatt & More) (Walter Schloss' 16 Investment Principles )

- Klarman’s book notes and Baupost strategy (Margin of Safety by Seth Klarman • Novel Investor) (Margin of Safety by Seth Klarman • Novel Investor)

- Buffett’s letters (Washington Post case) (Warren Buffett: WPC: From $10.6 Million to $221 Million | The Acquirer's Multiple®) and general value investing tenets (Why Seth Klarman Swears by the Margin of Safety).